The Composite Efficiency Score:

Why AI Needs Its Miles Per Gallon Moment?

Executive Summary

Artificial intelligence is often celebrated for being bigger and faster—more parameters, more tokens per second, more data. But these are the wrong quantities to worship. They tell us almost nothing about the only thing that actually matters: how efficiently a system turns energy into explanatory, useful thought.

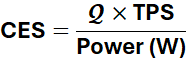

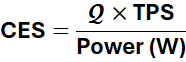

This essay proposes the Composite Efficiency Score (CES) as a new standard:

where Q is a composite quality measure (calibration, long-context understanding, reasoning), TPS is tokens per second, and W is power in watts. CES is, in essence, quality‑weighted tokens per joule—the cognitive analogue of lumens per watt.

By tying AI performance to physics instead of vanity metrics, CES changes the problem we are trying to solve. It makes brute-force scale and wasteful architectures look as crude as steam engines beside jet turbines. Under CES, “faster” at twice the power is not progress. Nor is “smarter” that collapses under long context or fails at reasoning. Only systems that produce high‑quality output, quickly, on little energy are rewarded.

This has profound consequences. It privileges architectural insight over parameter inflation, favors sparsity, dynamic computation, and genuine algorithmic advances, and exposes inefficiencies all the way down—from model design to hardware utilization. Like a nutrition label for intelligence, CES makes the hidden cost of cognition visible and comparable.

The central claim of this essay is not merely that CES is a better metric. It is that progress in AI should be measured as increasing explanatory power per joule. Once we adopt that standard, much of today’s AI practice will look, in retrospect, like flooring the accelerator of a badly tuned engine: noisy, impressive on paper—and fundamentally inefficient.

You know what’s interesting about a Ferrari?

Sure, it goes fast. That’s the headline number—0 to 60 in under three seconds, top speed over 200 mph. Very impressive. But that’s not really why people want a Ferrari.

It’s the whole experience. The throttle response—how instantly the engine answers when you ask for power. The way it handles corners. The precision of the steering. How it manages weight and aerodynamics. Even the sound of the engine is part of the engineering. A Ferrari isn’t just fast; it’s efficiently elegant. Every component working together to create something that feels right.

Now, artificial intelligence isn’t a car. But we’re measuring it like we only care about the speedometer.

Right now, when people talk about how good an AI system is, they mostly talk about tokens per second—how quickly it generates text. And don’t get me wrong, speed matters. Nobody wants to wait five minutes for an answer. But here’s what’s curious: we’ve gotten very good at making these systems fast, while the question of how efficiently they think—how elegantly they use their resources—has become almost an afterthought.

I started noticing this when I looked at the new architectures people are building. They have wonderful names—sparse attention mechanisms, continuous autoregressive models, dynamic memory compression. What they’re really doing is trying to make computation more efficient. Skip the redundant calculations. Only pay attention to what matters. Store memory cleverly instead of keeping everything.

These aren’t just tricks to go faster. They’re attempts to make the whole system work better—to think more like a well-engineered Ferrari and less like a muscle car with an oversized engine.

But we’re still mostly measuring them with the same simple metric: How many tokens per second?

It’s like judging that Ferrari purely by its top speed and ignoring everything else that makes it a Ferrari.

So I got curious: What if we measured AI systems the way we measure any well-engineered system? What if we looked at the complete picture—the quality of the output, the speed of delivery, and yes, the energy it takes to produce that result?

What if we cared about the efficiency of intelligence, not just its velocity?

The Three Things That Actually Matter

When you think about any efficient system—an engine, a solar panel, even your own body—there are really only three things that matter:

What you get out. (The quality of the work done)

How quickly you get it. (The speed of delivery)

What it costs to produce. (The energy consumed)

Everything else is just detail.

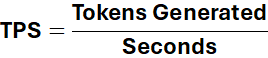

Now, with AI systems, we’ve gotten pretty good at measuring that middle one—speed. Tokens per second tells you how fast the system generates text. Great. But it tells you nothing about the other two.

Let me give you an example. Suppose I have two AI systems, and I ask them both a tricky question: “Explain why the sky is blue, but make it understandable to a five-year-old.”

System A spits out an answer in 0.5 seconds. Very fast! But the answer is technically correct yet completely incomprehensible to a child. It uses words like “Rayleigh scattering” and “wavelength-dependent refraction.”

System B takes 0.8 seconds—a bit slower. But it gives you: “The sky is like a big coloring book, and sunlight has all the colors mixed together. Blue is the bounciest color, so it bounces all around the sky while the other colors go more straight through.”

Which system is better?

If you only look at tokens per second, System A wins. But that’s absurd. System B actually solved the problem. It did the thinking we wanted.

So the first thing we need is a way to measure quality—not just “did it produce text?” but “did it produce useful text?” Did it reason well? Did it understand what was being asked? Did it give you something you can actually use?

That’s the quality dimension. Call it Q.

Now, speed still matters. All else being equal, faster is better. Nobody wants to wait. So we need to measure how quickly that quality arrives—tokens per second, sure, but weighted by whether those tokens are actually good. Fast garbage isn’t impressive. Fast insight is.

That’s the temporal dimension.

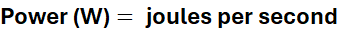

But here’s what’s really interesting—and this is the part people forget: All of this is happening in the physical world.

When an AI system thinks, electrons are moving. Transistors are switching. Heat is being generated. Power plants are burning fuel or spinning turbines or converting sunlight. There’s a very real thermodynamic cost to every computation.

Right now, asking a large AI model a complex question costs about the same energy as leaving a lightbulb on for an hour. That might not sound like much, until you realize these systems are answering billions of questions. Suddenly you’re talking about power consumption equivalent to a small city.

And that number keeps growing.

So the third thing—the one we’ve been mostly ignoring—is the energy cost. How many watts does it take to produce that quality at that speed?

That’s the thermodynamic dimension.

Now here’s where it gets elegant. If you want to measure how efficient a system really is, you need to look at all three of these together. Not as separate scores, but as a unified picture.

You want to know: How much high-quality intelligence can this system produce per unit of energy, and how fast can it deliver it?

That’s what we’re really after. That’s the efficiency of intelligence.

And it turns out, when you start looking at it this way, everything changes.

Why Energy Changes Everything

Here’s something I find beautiful about physics: you can’t cheat energy.

You can make accounting tricks. You can move costs around. You can optimize one part of a system while quietly making another part worse. But energy? Energy is honest. It’s the one thing you can’t fake.

If I tell you a system uses 100 watts, that’s real. There’s a meter on the wall measuring it. The power company is charging for it. The heat is dissipating into the room. You can’t pretend it away.

And that changes everything about how you think about efficiency.

Let me show you what I mean. Right now, if you want to make an AI system “better,” you have a few options:

You could make it bigger—more parameters, more memory, more of everything. This usually works. Bigger models tend to perform better. But they also consume more power. A lot more. The relationship isn’t linear; it’s worse than linear. Double the model size, and you might triple the energy cost.

Or you could make it faster—better hardware, optimized code, clever parallelization. This also usually works. But again, there’s an energy cost. Faster processors draw more power. Moving data around takes energy. Every transistor that switches is doing thermodynamic work.

Or—and this is the interesting option—you could make it smarter about what it computes.

See, here’s the thing about computation: not all of it is equally useful. When an AI system is working on a problem, a lot of what it’s doing is... well, let’s call it “busywork.” It’s computing things that don’t really matter for the final answer. It’s paying attention to irrelevant details. It’s recalculating things it already knows.

It’s like if you asked me to add up 2 + 2 + 2 + 2 + 2, and instead of thinking “that’s 5 times 2, which is 10,” I carefully computed 2 + 2 = 4, then 4 + 2 = 6, then 6 + 2 = 8, then 8 + 2 = 10. I’d get the right answer, but I’d be doing way more work than necessary.

The clever architectures I mentioned earlier—the sparse attention, the dynamic compression, all of that—they’re trying to skip the busywork. They’re trying to compute only what matters.

And here’s what’s fascinating: when you measure these systems by energy efficiency, suddenly that cleverness shows up in the metric.

A system that skips unnecessary computation doesn’t just save time—it saves watts. And when you’re measuring quality per watt, that cleverness becomes visible. It becomes something you can optimize for directly.

But there’s something even more interesting happening here.

When you make energy the constraint—when you say “you have this much power to work with, now show me the best thinking you can do”—you completely change the incentive structure.

You can’t just throw more hardware at the problem anymore. You can’t just make everything bigger and faster and hope it works out. You have to be clever. You have to be elegant. You have to design systems that achieve more with less.

It’s like the difference between building a muscle car and building a Formula 1 race car. The muscle car approach is: big engine, lots of power, go fast. The Formula 1 approach is: every gram matters, every surface is shaped for a reason, every component is engineered for efficiency.

Both can be fast. But only one is actually efficient.

And here’s the practical implication: if we start measuring AI systems this way—if we start caring about intelligence per watt—we create pressure toward better architecture, not just bigger scale.

We start rewarding the systems that think elegantly. The ones that solve problems with minimal waste. The ones that, like that Ferrari, aren’t just fast but feel right in how they work.

That’s not a small shift. That’s a fundamental change in how we approach building these systems.

What CES Actually Measures

Okay, so let’s build this thing.

We said we need three things: quality, speed, and energy cost. How do we combine them into something useful?

Well, let’s think about what we want. We want a system that produces high-quality output (Q), quickly (tokens per second, or TPS), while using minimal power (watts, W).

If you write that out as a simple relationship, you get:

Quality × Speed / Power

Or more formally: (Q × TPS) / W

That’s it. That’s the Composite Efficiency Score—CES for short.

Now, before you say “that seems too simple,” let me tell you why I think this is exactly right.

First, notice what happens when you improve each component:

Better quality (higher Q) → higher score

Faster delivery (higher TPS) → higher score

Lower power consumption (lower W) → higher score

That’s what we want. The metric points in the right direction.

But here’s what’s more interesting: notice what you can’t do with this metric.

You can’t cheat by making low-quality output really fast. Because Q is in the numerator—if quality drops, your score drops proportionally.

You can’t cheat by cranking up the power to go faster. Because W is in the denominator—if you’re using twice the power to go twice as fast, you’re not actually more efficient. The TPS and W cancel out.

You can’t optimize just one dimension and call it a day. To improve CES, you have to improve the whole system.

Now, let’s think about what this score actually means physically.

The numerator—Q × TPS—is measuring “useful intelligence delivered per second.” It’s a rate. How much high-quality thinking is this system producing per unit time?

The denominator—W—is power. Joules per second.

So CES is really measuring: How much useful intelligence do you get per joule of energy?

That’s a beautiful thing to measure. It’s the efficiency of converting energy into thought.

Think about it this way: When you turn on a lightbulb, you’re converting electrical energy into light. We measure that efficiency in lumens per watt—how much visible light do you get per unit of power? A good LED bulb might give you 100 lumens per watt. An old incandescent gives you maybe 15.

CES is the same idea, but for intelligence. How much useful cognitive work do you get per watt?

And just like with lightbulbs, this measurement creates a natural pressure toward better design. When someone invented LEDs, they didn’t just make bulbs brighter—they made them fundamentally more efficient at converting energy to light. New architecture, not just more power.

That’s what CES does for AI. It creates pressure toward systems that are fundamentally better at converting energy into intelligence.

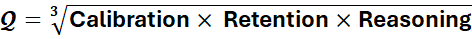

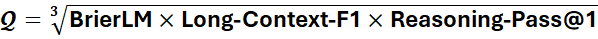

Now, here’s something important: Q isn’t just a single number. Remember, we’re measuring quality across multiple dimensions—can it reason? Can it understand what you’re asking? Does it give useful answers?

The way we handle this is by taking the geometric mean of these quality measures. That’s just a fancy way of saying: the system has to be good at all of them. You can’t compensate for being terrible at reasoning by being great at something else. The geometric mean keeps you honest.

This matters because modern AI systems are increasingly hybrid architectures. They’re not just doing one thing; they’re combining multiple approaches—some parts handle retrieval, some handle reasoning, some handle generation. CES naturally evaluates the whole system’s efficiency, not just individual components.

So when you see a CES score, you’re seeing something fundamental: How efficiently does this system convert electrical power into useful intelligence?

High CES means elegant architecture, clever computation, minimal waste.

Low CES means brute force, inefficient design, lots of energy for modest results.

And here’s what I find most compelling: this isn’t just a metric. It’s a forcing function toward better AI.

The Mathematics of Intelligence Efficiency

Traditional benchmarks answer can the model think?

CES answers a new question:

How much intelligence can the system produce per unit energy?

Formally,

Now, we have to be rigorous about Q (Quality). You can’t just average a bunch of test scores. If a Ferrari has a world-class engine but no steering wheel, it’s not a “50% good car,” it’s a death trap. The system requires harmony.

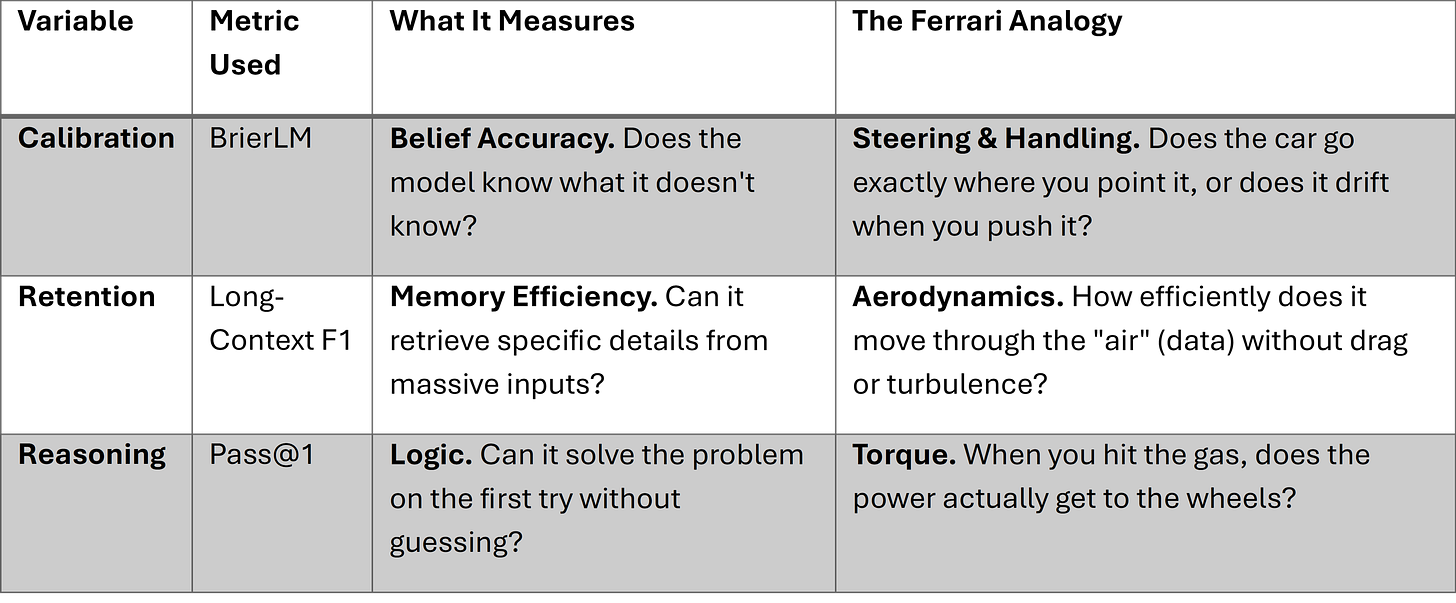

Therefore, $Q$ is calculated as the geometric mean of three foundational components. We use the geometric mean because it penalizes imbalance; if any single component drops to zero, the entire score collapses.

Where:

A higher CES means more useful cognition per watt, capturing the quality, speed, and cost of intelligence expression. This isn’t just elegant theory, every term is measurable with existing infrastructure.

Notice what happens when someone tries to ‘game’ CES by optimizing one dimension. Improving BrierLM alone while letting reasoning accuracy slip? The geometric mean in Q penalizes that immediately. Cranking up power to double TPS? The denominator cancels the gain. CES forces balanced optimization.

Just as a Ferrari’s performance emerges from the harmony of engine, suspension, aerodynamics, and steering, Q emerges from the harmony of calibration, comprehension, and reasoning. Excellence in one without the others isn’t intelligence—it’s imbalance.

Note *: BrierLM = 1 - (mean_bs / max_bs), So BrierLM is not a loss — it is a calibration quality score.

Note **: Just as a Ferrari’s performance emerges from the harmony of engine, suspension, aerodynamics, and steering, Q emerges from the harmony of calibration, comprehension, and reasoning. Excellence in one without the others isn’t intelligence, it’s imbalance.

The Hardware Control

There is one final, crucial constraint.

In Formula 1, you can’t compare a driver’s time on a straightaway to a driver’s time on a winding mountain road. You need a standard track.

Similarly, you cannot measure CES effectively if one model is running on a vintage laptop and another is running on a brand-new H100 cluster. The hardware distorts the wattage.

Therefore, CES must be reported on Standardized Reference Hardware (e.g., a single standardized GPU or a fixed FLOP budget). This isolates the architecture’s efficiency from the hardware’s raw power.

When you control for hardware, a higher CES score proves something profound: the system isn’t just winning because it has a bigger engine. It’s winning because it has a better design.

What This Changes

Here’s what’s interesting about metrics: they shape behavior.

I don’t mean that in some abstract way. I mean it very literally. When you measure something, people optimize for it. They can’t help it. It’s human nature. Show me what you’re measuring, and I’ll show you what people will build.

Right now, we mostly measure AI systems by their performance on benchmarks—how accurately they answer questions, how well they score on tests. And secondarily, we measure speed. So what do people build? Bigger models that score higher on benchmarks and run faster on specialized hardware.

This has worked remarkably well, actually. The systems have gotten impressively capable. But we’re starting to hit limits. The models are getting so large and so power-hungry that the practical question becomes: Can we actually afford to run this thing?

Now imagine we start measuring CES instead.

Suddenly, the game changes completely.

Let’s say you’re a researcher trying to improve your AI system. Under the old metrics, your options were straightforward: make the model bigger, get more training data, use faster processors. More scale, more compute, more power.

But under CES? Those approaches only work if they improve efficiency. Adding more parameters might increase quality (Q goes up), but it definitely increases power consumption (W goes up). Does Q increase faster than W? If not, your CES actually goes down. You’ve made the system worse by the metric that matters.

So what would you do instead?

Well, you’d start looking for places where your system is doing unnecessary work. Maybe it’s computing attention over every single token when it only really needs to focus on a few. Maybe it’s storing redundant information in memory. Maybe it’s recalculating things it already figured out.

You’d start asking: Where can I be smarter instead of just bigger?

And this leads to genuinely different architectures. Not just “let’s make the existing transformer bigger,” but “let’s rethink how we do computation entirely.“

Some examples that are already emerging:

Sparse attention mechanisms only compute relationships between tokens that are likely to matter. Instead of comparing every word to every other word (which scales terribly), they’re selective. They’re clever. This reduces both computation and energy.

Continuous models that don’t discretize everything into tokens. They work more like analog systems—smoother, more efficient for certain types of problems.

Dynamic compression that figures out what information actually needs to be kept in memory versus what can be safely forgotten or compressed. Your brain does this constantly. Most AI systems don’t.

Hybrid architectures that route different types of problems to different types of processors—not just “throw everything at the biggest GPU we have,” but “use the right tool for each job.”

What all of these have in common is that they’re trying to do less computation while maintaining or improving quality. They’re optimizing for efficiency, not just scale.

And here’s what I find fascinating: many of these approaches were already being explored. But they were often seen as secondary concerns—interesting ideas, but not the main thrust of research. CES would make them primary concerns. It would make efficiency the thing everyone cares about.

There’s another implication too, and it’s more subtle.

When you optimize for CES, you can’t just focus on the AI model itself. You have to think about the whole system—the model, the hardware it runs on, how data moves through memory, how different components coordinate.

A high-CES system isn’t just a good model running on standard hardware. It’s a model and hardware designed together, co-optimized for efficiency. Like how a Formula 1 car isn’t just a good engine bolted onto a chassis, the entire vehicle is designed as one integrated system.

This pushes AI development toward something more like systems engineering and less like pure machine learning research. You need people who understand not just algorithms, but thermodynamics, hardware architecture, memory hierarchies. You need people thinking about the whole picture.

And perhaps most importantly: CES makes sustainability measurable.

Right now, when someone says “we need to build greener AI,” it’s somewhat vague. What does that mean exactly? Use renewable energy? Sure, but that doesn’t change how much energy the system uses. It just changes where the energy comes from.

CES makes it concrete: build systems that do more with less. Period. It doesn’t matter if your energy comes from solar panels—if your system is inefficient, it has a low CES. The metric forces you to address the fundamental issue: computational efficiency.

This matters more than you might think. AI is starting to consume a meaningful fraction of global electricity. If we keep scaling the way we have been, that fraction will only grow. At some point, it becomes a real societal question: Is this the best use of that energy?

But if we optimize for CES, if we build systems that are truly efficient; that question becomes much easier to answer. Yes, we’re using energy, but we’re using it incredibly well. We’re getting enormous value per watt.

That’s the world CES points toward: AI systems that are not just powerful, but elegant. Not just fast, but efficient. Not just intelligent, but wise about how they use their resources.

I think that’s a world worth building.

Where CES Can Mislead (and How to Use It Anyway)

CES is a demanding metric, but it isn’t a perfect ruler. It doesn’t claim to measure “intelligence” in any metaphysical sense, and it inherits all the biases and blind spots of the things we choose to measure. A system with a high CES is efficient at turning energy into the particular kinds of cognitive work we decided to put into Q—nothing more, nothing less.

That’s important to say out loud, because if CES ever becomes a number people optimize for, it will be subject to exactly the same forces as every other metric: Goodhart’s Law. Once a measure becomes a target, it stops being a good measure. So if we want CES to be genuinely useful, we have to be clear about where it can mislead.

The first limitation is Q itself. The quality term is not an oracle; it’s a construct. It bundles together calibration (Brier), retrieval fidelity (long-context F1), and reasoning accuracy (Pass@1). Those are good choices, but they are still choices. Change the benchmarks, or the domains they’re drawn from, and Q will move. In that sense, CES is grounded in physics on the denominator side—the joules are real—but grounded in judgment on the numerator side. You should treat the structure of CES (quality × speed / power) as stable, while fully expecting the definition of “quality” to evolve over time as our benchmarks get better.

The second limitation is gaming. If CES becomes a leaderboard number, people will try to win the leaderboard. You can imagine aggressively quantized models that generate tokens extremely quickly at very low power, nudging Q just high enough to look respectable. You can imagine architectures tuned to do spectacularly well on a small set of known benchmarks without actually being robust in the wild. The geometric mean inside Q is a partial defense here, it punishes one-dimensional models that are great at one thing and terrible at others—but it’s not magic. The only real protection is to keep Q broad, refresh it regularly, and publish the individual sub-scores (calibration, context, reasoning) alongside the composite so you can see where a system is “cheating.”

Third, CES is workload- and hardware-dependent. It is not a universal IQ score for models. The same model will have a very different CES when serving short chat bursts versus long-form reasoning, batch inference versus interactive tools. Likewise, the same weights will look more or less efficient depending on whether they’re running on an H100 cluster, a TPU pod, or a consumer GPU with poor memory bandwidth. In practice, CES is most honest in two modes: (1) comparing different models on the same hardware under a clearly specified workload, or (2) comparing different hardware running the same model and workload. As soon as you start cross-comparing “Model A on Stack X” versus “Model B on Stack Y” without normalization, you’re measuring whole-system efficiency, not just architectural elegance—and you should say so.

Finally, CES doesn’t capture everything that matters. It says nothing directly about safety, alignment, or harm. A model could, in principle, be extraordinarily efficient at producing very bad outcomes. It also doesn’t account for tail latency, UX qualities, or resilience under adversarial input. Those deserve their own metrics. The right way to think about CES is as one panel on a broader “AI nutrition label”: a physics-grounded axis that tells you how well a system converts energy into useful cognitive work. You’d never buy a car on miles-per-gallon alone, but you’d be suspicious of a car that refused to publish its fuel economy. CES should play a similar role for AI: not the whole story, but a number you’d be uncomfortable not knowing.

The Right Question

You know what I love about good metrics? They make you ask better questions.

Before we had “miles per gallon,” people argued about cars in vague terms. “This one’s better.” “No, that one is.” Better at what? Faster? More powerful? It was all a bit fuzzy.

Then someone measured fuel efficiency, and suddenly the conversation got clear. You could compare a compact car to a truck and actually discuss the tradeoffs intelligently. Neither was “better”—they were designed for different purposes, and you could see that in the numbers.

That’s what CES does for AI. It doesn’t tell you which system is “best.” It tells you something more useful: How efficiently is this system converting energy into useful intelligence?

And once you can measure that, you can start having much more interesting conversations.

Instead of “How do we make the biggest model?” you ask “How do we make the most efficient model?”

Instead of “How fast can we go?” you ask “How elegantly can we think?”

Instead of “How much compute do we need?” you ask “How little compute can we get away with?”

These are better questions. They lead to better engineering.

Now, I should say: CES isn’t perfect. No metric is. There are details to work out—exactly how to measure quality across different domains, how to account for different types of workloads, how to compare systems fairly. That’s fine. That’s how science works. You propose something, people refine it, it gets better.

But the core idea, measuring intelligence per watt, that’s sound. It’s grounded in physics. It can’t be faked. And it points in the right direction.

Here’s what I think will happen: As these systems get more powerful and more widely used, energy will become impossible to ignore. Not for moral reasons (though those matter), but for practical ones. At some point, the power bill becomes a real constraint. The cooling requirements become prohibitive. The infrastructure demands become too large.

When that happens and I think it’s happening now; we’ll need a way to measure efficiency that actually means something. We’ll need CES, or something very much like it.

And then maybe, just maybe, we’ll start building AI systems the way we should have been building them all along: not just making them bigger and faster, but making them smarter about how they work.

Not muscle cars. Ferraris.

That’s the goal, anyway. We’ll see what happens.

But I’ll tell you this: It’s a lot more interesting to optimize for efficiency than it is to optimize for size. And the systems that come out of that kind of thinking?

Those will be something to see.

I really learned a lot. Very outside of my domain but it really forced me outside of my comfort zone.